Águeda Simó

Stereoscopic techniques help to perceive spatial depth, hence they are used to create realistic representations of the three-dimensional world. However, they can be used to manipulate spatial dimensions and create ambiguous and impossible worlds. The video installation Eccentric Spaces shows the plasticity of stereo depth and its immersive qualities, how stereo depth can be manipulated to create eccentric dimensions and reveal hidden worlds that only exist within the stereoscopic projections.

Acknowledgements

karrantza Town Hal, Basque Country, where Pozalalagua Cave is located; Image Processing Group (GTI, Grupo

de Tratamiento de Imágenes) of the Technical University of Madrid.

The exhibition of Eccentric Spaces at Museum of Guarda, Portugal, was supported by the University of Beira Interior.

* Nicola Tisato et al. (2015) Microbial Mediation of Complex Subterranean Mineral Structures

www.nature.com/scientificreports

"Helictites—an enigmatic type of mineral structure occurring in some caves—differ from classical

speleothems as they develop with orientations that defy gravity. While theories for helictite

formation have been forwarded, their genesis remains equivocal. Here, we show that a remarkable

suite of helictites occurring in Asperge Cave (France) are formed by biologically-mediated processes,

rather than abiotic processes as had hitherto been proposed. Morphological and petro-physical

properties are inconsistent with mineral precipitation under purely physico-chemical control.

Instead, microanalysis and molecular-biological investigation reveals the presence of a prokaryotic

biofilm intimately associated with the mineral structures. We propose that microbially-influenced

mineralization proceeds within a gliding biofilm which serves as a nucleation site for CaCO3, and

where chemotaxis influences the trajectory of mineral growth, determining the macroscopic

morphology of the speleothems. The influence of biofilms may explain the occurrence of similar

speleothems in other caves worldwide, and sheds light on novel biomineralization processes."

Eccentric Spaces

Spatial Dimensions and Stereo Depth

The romance between spatial dimensions has intrigued not only mathematicians and physicists but artists as well. The mathematician Edwin Abbott explained in Flatland the paradox of how, we live in a world of higher dimensions but we are not able to perceive them. His example of a sphere that, when passing through a plane, is mistaken for a circle that is growing—or shrinking—is an elegant metaphor that we can understand because it involves lower dimensions. Theoretical physicists Lisa Randall and Michio Kaku mention this romance between dimensions when explaining their research on higher and lower dimensions that, although we cannot perceive, could exist. Graphic artist M. C. Escher depicted the ambiguity of spatial dimensions revealing paradoxical worlds,—that introduces uncertainty not only in the representation of three-dimensional spaces in two-dimensional surfaces, but in our concepts of physical dimensions, and thus, in reality itself. The intersection of the three-dimensional world with a bidimensional surface can be explored using stereoscopic techniques to expand spatial depth on a flat surface.

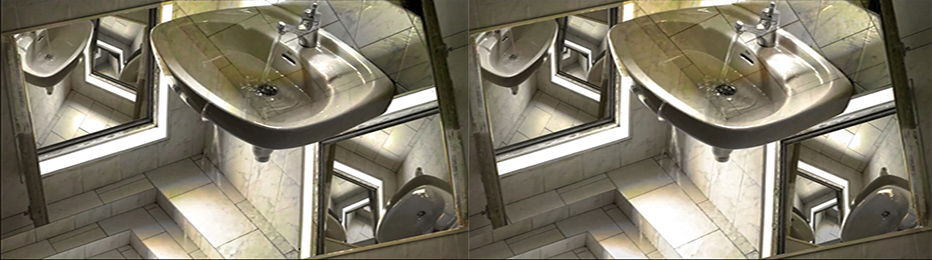

Stereoscopic techniques are fascinating because they create immaterial entities that seem to be tangible. They can create the illusion of depth without any other visual cues as Béla Julesz demonstrated with random-dot stereograms. However, depth perception is a complex neurological process and our visual experience and memories together with pictorial cues— such as texture gradient and occlusion—are important factors that cannot be left apart when representing spatial dimensions. Thus, the stereoscopic re/deconstruction of a known, familiar physical space, such as a room, can only work if we carefully merge together both stereoscopic techniques and pictorial cues; otherwise pictorial cues can override stereopsis and the illusion of depth can be lost. But what would happen if we intentionally use monocular and binocular cues in contradictory relationships? Or if we intentionally reverse or turn inside out the stereoscopic depth relations?

The plasticity of stereo depth in combination with pictorial cues, allows the manipulation of spatial dimensions and the exploration of spatial effects, that otherwise would be impossible to achieve, to create impossible worlds and unveil unseen dimensions. Stereoscopic images can have negative parallax (the space that emerges from the screen), positive parallax (the space that draws you beyond the screen) and zero parallax (the space that has no stereoscopic depth). These three parallaxes—determined by the convergence of left and right images—are all necessary because they work together along the viewer's perceptual processes to create a continuous depth. One cannot exist without the other, because in order to immerse viewers in the artwork we need to recreate the spatial perception experienced in physical reality where depth manifests itself as a continuous space. However, their relationship can be articulated in an eccentric fashion, contradicting the classical representations of space ruled by the renaissance perspective.

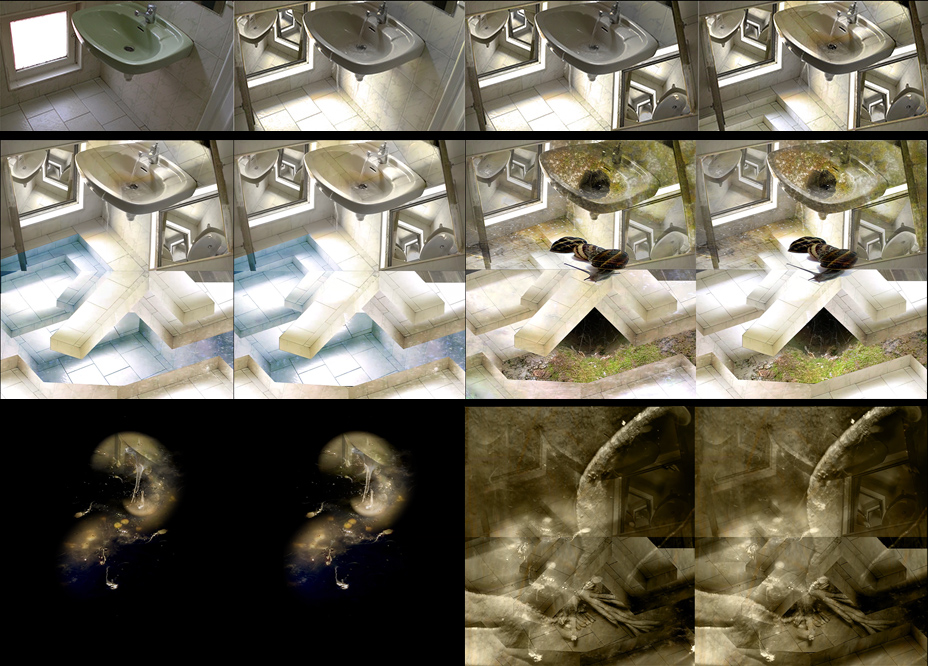

The Process

I developed a low cost stereoscopic projection system with two screens—a vertical one and a horizontal one—to de/re-construct the physical dimensions of a room. It is important to note that both projections—vertical and horizontal—are composed by using only stereoscopic live action footage of the flat's room. Thus, it is not a simulation of a room but the real room. This is the narrative of the installation: the observer own perception, who is confronted to a dual space. I used a long static shot, that is, a single point of view, to emulate the continuity of human perception and create the impression of looking through a window into another world. This type of shot creates an atmosphere of calm and serenity and draws more attention to the nature of the scenery in which organic elements and water are in perpetual motion.

To create this eccentric space, the moving images were cut into pieces to compose both the wall and floor projections, the latter totally created from scratch using pieces of the former. Thus, it was necessary to keep the continuity not only between both projections but also among all the pieces used in the composition. To accomplish such continuity, every object's convergence and pictorial cues—such as luminosity and size—had to be independently treated but according to the whole scene depth effect. This was a delicate and very demanding process, because of the inherent problems of stereoscopic images—e.g. the loss of stereopsis with vertical parallax or incorrect horizontal parallax—that could lead to an incorrect or broken perception of the stereoscopic space. The fluid and organic elements that appear in the videos—such as water drops, jelly fishes, snails or eccentric stalatics(*)—were recorded separately. As it can be seen in the stereoscopic samples, the illusionary space that protrudes and expands behind the screen, though impossible according to the laws of physics, does not appear to be broken or stereoscopically incorrect. Moreover, such stereoscopic space intertwines and unfolds its dimensions—up and down, left and right, back and forth— in awkward directions, creating a paradox that contradicts our concepts of physical dimensions